In World War II, Britain was fighting for its survival against German aerial bombardment. Yet Britain was importing dyes from Germany at the same time. This sounds curious, to put it mildly. How can two countries at war with each other also be trading goods?

Examples of this abound, actually. Britain also traded with its enemies for almost all of World War I. India and Pakistan conducted trade with each other during the First Kashmir War, from 1947 to 1949, and during the India-Pakistan War of 1965. Croatia and then-Yugoslavia traded with each other while fighting in 1992.

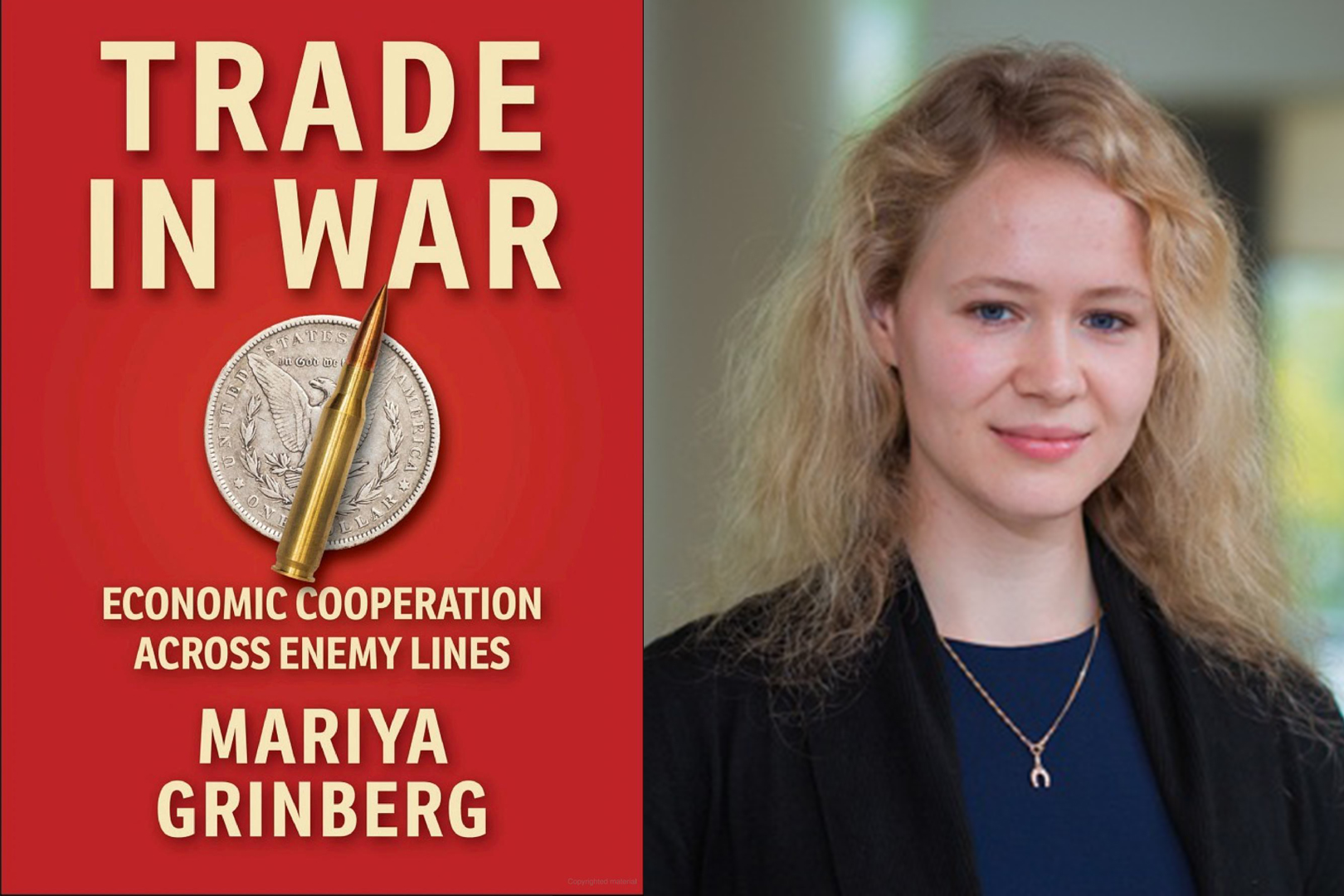

“States do in fact trade with their enemies during wars,” says MIT political scientist Mariya Grinberg. “There is a lot of variation in which products get traded, and in which wars, and there are differences in how long trade lasts into a war. But it does happen.”

Indeed, as Grinberg has found, state leaders tend to calculate whether trade can give them an advantage by boosting their own economies while not supplying their enemies with anything too useful in the near term.

“At its heart, wartime trade is all about the tradeoff between military benefits and economic costs,” Grinberg says. “Severing trade denies the enemy access to your products that could increase their military capabilities, but it also incurs a cost to you because you’re losing trade and neutral states could take over your long-term market share.” Therefore, many countries try trading with their wartime foes.

Grinberg explores this topic in a groundbreaking new book, the first one on the subject, “Trade in War: Economic Cooperation Across Enemy Lines,” published this month by Cornell University Press. It is also the first book by Grinberg, an assistant professor of political science at MIT.

Calculating time and utility

“Trade in War” has its roots in research Grinberg started as a doctoral student at the University of Chicago, where she noticed that wartime trade was a phenomenon not yet incorporated into theories of state behavior.

Grinberg wanted to learn about it comprehensively, so, as she quips, “I did what academics usually do: I went to the work of historians and said, ‘Historians, what have you got for me?’”

Modern wartime trading began during the Crimean War, which pitted Russia against France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and other allies. Before the war’s start in 1854, France had paid for many Russian goods that could not be shipped because ice in the Baltic Sea was late to thaw. To rescue its produce, France then persuaded Britain and Russia to adopt “neutral rights,” codified in the 1856 Declaration of Paris, which formalized the idea that goods in wartime could be shipped via neutral parties (sometimes acting as intermediaries for warring countries).

“This mental image that everyone has, that we don’t trade with our enemies during war, is actually an artifact of the world without any neutral rights,” Grinberg says. “Once we develop neutral rights, all bets are off, and now we have wartime trade.”

Overall, Grinberg’s systematic analysis of wartime trade shows that it needs to be understood on the level of particular goods. During wartime, states calculate how much it would hurt their own economies to stop trade of certain items; how useful specific products would be to enemies during war, and in what time frame; and how long a war is going to last.

“There are two conditions under which we can see wartime trade,” Grinberg says. “Trade is permitted when it does not help the enemy win the war, and it’s permitted when ending it would damage the state’s long-term economic security, beyond the current war.”

Therefore a state might export diamonds, knowing an adversary would need to resell such products over time to finance any military activities. Conversely, states will not trade products that can quickly convert into military use.

“The tradeoff is not the same for all products,” Grinberg says. “All products can be converted into something of military utility, but they vary in how long that takes. If I’m expecting to fight a short war, things that take a long time for my opponent to convert into military capabilities won’t help them win the current war, so they’re safer to trade.” Moreover, she adds, “States tend to prioritize maintaining their long-term economic stability, as long as the stakes don’t hit too close to home.”

This calculus helps explain some seemingly inexplicable wartime trade decisions. In 1917, three years into World War I, Germany started trading dyes to Britain. As it happens, dyes have military uses, for example as coatings for equipment. And World War I, infamously, was lasting far beyond initial expectations. But as of 1917, German planners thought the introduction of unrestricted submarine warfare would bring the war to a halt in their favor within a few months, so they approved the dye exports. That calculation was wrong, but it fits the framework Grinberg has developed.

States: Usually wrong about the length of wars

“Trade in War” has received praise from other scholars in the field. Michael Mastanduno of Dartmouth College has said the book “is a masterful contribution to our understanding of how states manage trade-offs across economics and security in foreign policy.”

For her part, Grinberg notes that her work holds multiple implications for international relations — one being that trade relationships do not prevent hostilities from unfolding, as some have theorized.

“We can’t expect even strong trade relations to deter a conflict,” Grinberg says. “On the other hand, when we learn our assumptions about the world are not necessarily correct, we can try to find different levers to deter war.”

Grinberg has also observed that states are not good, by any measure, at projecting how long they will be at war.

“States very infrequently get forecasts about the length of war right,” Grinberg says. That fact has formed the basis of a second, ongoing Grinberg book project.

“Now I’m studying why states go to war unprepared, why they think their wars are going to end quickly,” Grinberg says. “If people just read history, they will learn almost all of human history works against this assumption.”

At the same time, Grinberg thinks there is much more that scholars could learn specifically about trade and economic relations among warring countries — and hopes her book will spur additional work on the subject.

“I’m almost certain that I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface with this book,” she says.