A lot of attention has been paid to how climate change can drive biodiversity loss. Now, MIT researchers have shown the reverse is also true: Reductions in biodiversity can jeopardize one of Earth’s most powerful levers for mitigating climate change.

In a paper published in PNAS, the researchers showed that following deforestation, naturally-regrowing tropical forests, with healthy populations of seed-dispersing animals, can absorb up to four times more carbon than similar forests with fewer seed-dispersing animals.

Because tropical forests are currently Earth’s largest land-based carbon sink, the findings improve our understanding of a potent tool to fight climate change.

“The results underscore the importance of animals in maintaining healthy, carbon-rich tropical forests,” says Evan Fricke, a research scientist in the MIT Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the lead author of the new study. “When seed-dispersing animals decline, we risk weakening the climate-mitigating power of tropical forests.”

Fricke’s co-authors on the paper include César Terrer, the Tianfu Career Development Associate Professor at MIT; Charles Harvey, an MIT professor of civil and environmental engineering; and Susan Cook-Patton of The Nature Conservancy.

The study combines a wide array of data on animal biodiversity, movement, and seed dispersal across thousands of animal species, along with carbon accumulation data from thousands of tropical forest sites.

The researchers say the results are the clearest evidence yet that seed-dispersing animals play an important role in forests’ ability to absorb carbon, and that the findings underscore the need to address biodiversity loss and climate change as connected parts of a delicate ecosystem rather as separate problems in isolation.

“It’s been clear that climate change threatens biodiversity, and now this study shows how biodiversity losses can exacerbate climate change,” Fricke says. “Understanding that two-way street helps us understand the connections between these challenges, and how we can address them. These are challenges we need to tackle in tandem, and the contribution of animals to tropical forest carbon shows that there are win-wins possible when supporting biodiversity and fighting climate change at the same time.”

Putting the pieces together

The next time you see a video of a monkey or bird enjoying a piece of fruit, consider that the animals are actually playing an important role in their ecosystems. Research has shown that by digesting the seeds and defecating somewhere else, animals can help with the germination, growth, and long-term survival of the plant.

Fricke has been studying animals that disperse seeds for nearly 15 years. His previous research has shown that without animal seed dispersal, trees have lower survival rates and a harder time keeping up with environmental changes.

“We’re now thinking more about the roles that animals might play in affecting the climate through seed dispersal,” Fricke says. “We know that in tropical forests, where more than three-quarters of trees rely on animals for seed dispersal, the decline of seed dispersal could affect not just the biodiversity of forests, but how they bounce back from deforestation. We also know that all around the world, animal populations are declining.”

Regrowing forests is an often-cited way to mitigate the effects of climate change, but the influence of biodiversity on forests’ ability to absorb carbon has not been fully quantified, especially at larger scales.

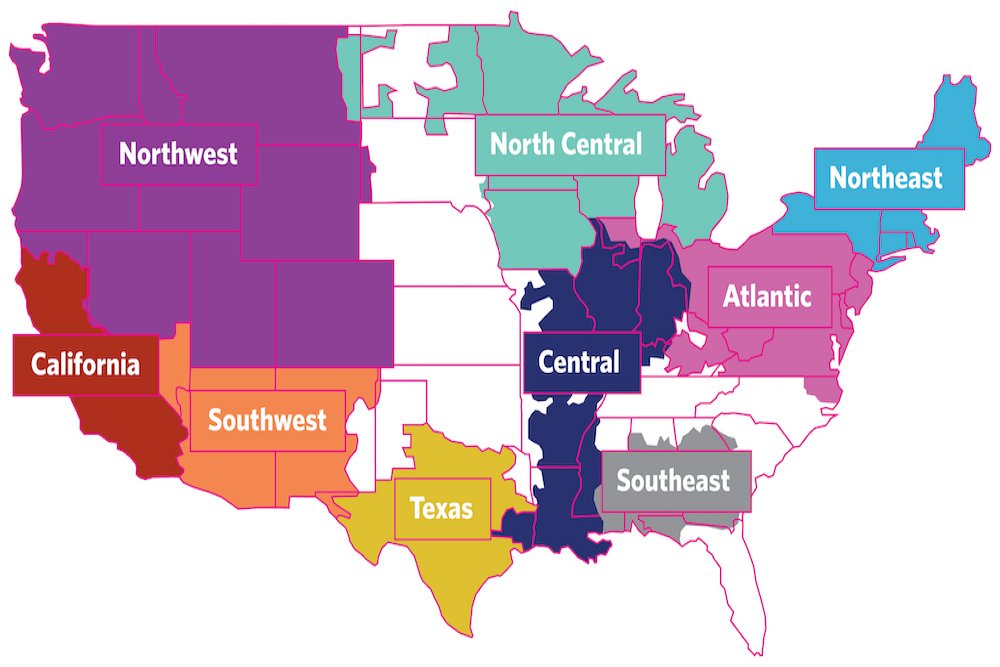

For their study, the researchers combined data from thousands of separate studies and used new tools for quantifying disparate but interconnected ecological processes. After analyzing data from more than 17,000 vegetation plots, the researchers decided to focus on tropical regions, looking at data on where seed-dispersing animals live, how many seeds each animal disperses, and how they affect germination.

The researchers then incorporated data showing how human activity impacts different seed-dispersing animals’ presence and movement. They found, for example, that animals move less when they consume seeds in areas with a bigger human footprint.

Combining all that data, the researchers created an index of seed-dispersal disruption that revealed a link between human activities and declines in animal seed dispersal. They then analyzed the relationship between that index and records of carbon accumulation in naturally regrowing tropical forests over time, controlling for factors like drought conditions, the prevalence of fires, and the presence of grazing livestock.

“It was a big task to bring data from thousands of field studies together into a map of the disruption of seed dispersal,” Fricke says. “But it lets us go beyond just asking what animals are there to actually quantifying the ecological roles those animals are playing and understanding how human pressures affect them.”

The researchers acknowledged that the quality of animal biodiversity data could be improved and introduces uncertainty into their findings. They also note that other processes, such as pollination, seed predation, and competition influence seed dispersal and can constrain forest regrowth. Still, the findings were in line with recent estimates.

“What’s particularly new about this study is we’re actually getting the numbers around these effects,” Fricke says. “Finding that seed dispersal disruption explains a fourfold difference in carbon absorption across the thousands of tropical regrowth sites included in the study points to seed dispersers as a major lever on tropical forest carbon.”

Quantifying lost carbon

In forests identified as potential regrowth sites, the researchers found seed-dispersal declines were linked to reductions in carbon absorption each year averaging 1.8 metric tons per hectare, equal to a reduction in regrowth of 57 percent.

The researchers say the results show natural regrowth projects will be more impactful in landscapes where seed-dispersing animals have been less disrupted, including areas that were recently deforested, are near high-integrity forests, or have higher tree cover.

“In the discussion around planting trees versus allowing trees to regrow naturally, regrowth is basically free, whereas planting trees costs money, and it also leads to less diverse forests,” Terrer says. “With these results, now we can understand where natural regrowth can happen effectively because there are animals planting the seeds for free, and we also can identify areas where, because animals are affected, natural regrowth is not going to happen, and therefore planting trees actively is necessary.”

To support seed-dispersing animals, the researchers encourage interventions that protect or improve their habitats and that reduce pressures on species, ranging from wildlife corridors to restrictions on wildlife trade. Restoring the ecological roles of seed dispersers is also possible by reintroducing seed-dispersing species where they’ve been lost or planting certain trees that attract those animals.

The findings could also make modeling the climate impact of naturally regrowing forests more accurate.

“Overlooking the impact of seed-dispersal disruption may overestimate natural regrowth potential in many areas and underestimate it in others,” the authors write.

The researchers believe the findings open up new avenues of inquiry for the field.

“Forests provide a huge climate subsidy by sequestering about a third of all human carbon emissions,” Terrer says. “Tropical forests are by far the most important carbon sink globally, but in the last few decades, their ability to sequester carbon has been declining. We will next explore how much of that decline is due to an increase in extreme droughts or fires versus declines in animal seed dispersal.”

Overall, the researchers hope the study helps improves our understanding of the planet’s complex ecological processes.

“When we lose our animals, we’re losing the ecological infrastructure that keeps our tropical forests healthy and resilient,” Fricke says.

The research was supported by the MIT Climate and Sustainability Consortium, the Government of Portugal, and the Bezos Earth Fund.