If your hand lotion is a bit runnier than usual coming out of the bottle, it might have something to do with the goop’s “mechanical memory.”

Soft gels and lotions are made by mixing ingredients until they form a stable and uniform substance. But even after a gel has set, it can hold onto “memories,” or residual stress, from the mixing process. Over time, the material can give in to these embedded stresses and slide back into its former, premixed state. Mechanical memory is, in part, why hand lotion separates and gets runny over time.

Now, an MIT engineer has devised a simple way to measure the degree of residual stress in soft materials after they have been mixed, and found that common products like hair gel and shaving cream have longer mechanical memories, holding onto residual stresses for longer periods of time than manufacturers might have assumed.

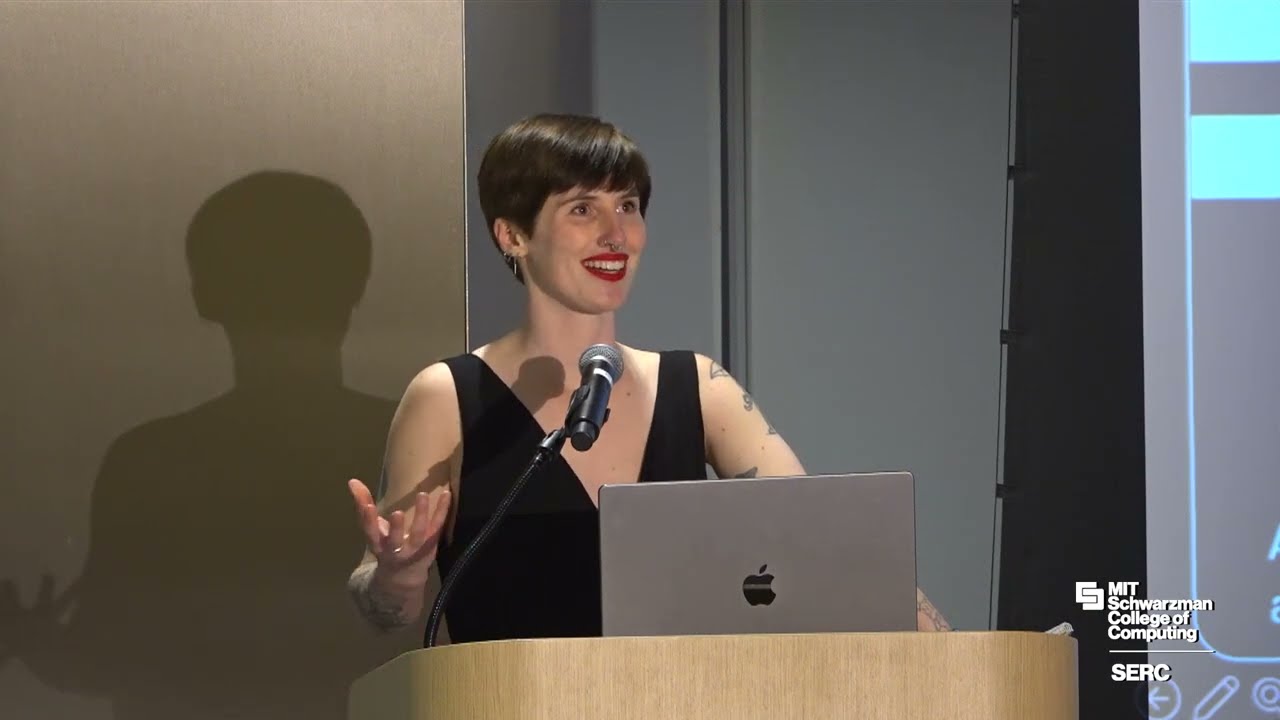

In a study appearing today in Physical Review Letters, Crystal Owens, a postdoc in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), presents a new protocol for measuring residual stress in soft, gel-like materials, using a standard benchtop rheometer.

Applying this protocol to everyday soft materials, Owens found that if a gel is made by mixing it in one direction, once it settles into a stable and uniform state, it effectively holds onto the memory of the direction in which it is mixed. Even after several days, the gel will hold some internal stress that, if released, will cause the gel to shift in the direction opposite to how it was initially mixed, reverting back to its earlier state.

“This is one reason different batches of cosmetics or food behave differently even if they underwent ‘identical’ manufacturing,” Owens says. “Understanding and measuring these hidden stresses during processing could help manufacturers design better products that last longer and perform more predictably.”

A soft glass

Hand lotion, hair gel, and shaving cream all fall under the category of “soft glassy materials” — materials that exhibit properties of both solids and liquids.

“Anything you can pour into your hand and it forms a soft mound is going to be considered a soft glass,” Owens explains. “In materials science, it’s considered a soft version of something that has the same amorphous structure as glass.”

In other words, a soft glassy material is a strange amalgam of a solid and a liquid. It can be poured out like a liquid, and it can hold its shape like a solid. Once they are made, these materials exist in a delicate balance between solid and liquid. And Owens wondered: For how long?

“What happens to these materials after very long times? Do they finally relax or do they never relax?” Owens says. “From a physics perspective, that’s a very interesting concept: What is the essential state of these materials?”

Twist and hold

In the manufacturing of soft glassy materials such as hair gel and shampoo, ingredients are first mixed into a uniform product. Quality control engineers then let a sample sit for about a minute — a period of time that they assume is enough to allow any residual stresses from the mixing process dissipate. In that time, the material should settle into a steady, stable state, ready for use.

But Owens suspected that the materials may hold some degree of stress from the production process long after they’ve appeared to settle.

“Residual stress is a low level of stress that’s trapped inside a material after it’s come to a steady state,” Owens says. “This sort of stress has not been measured in these sorts of materials.”

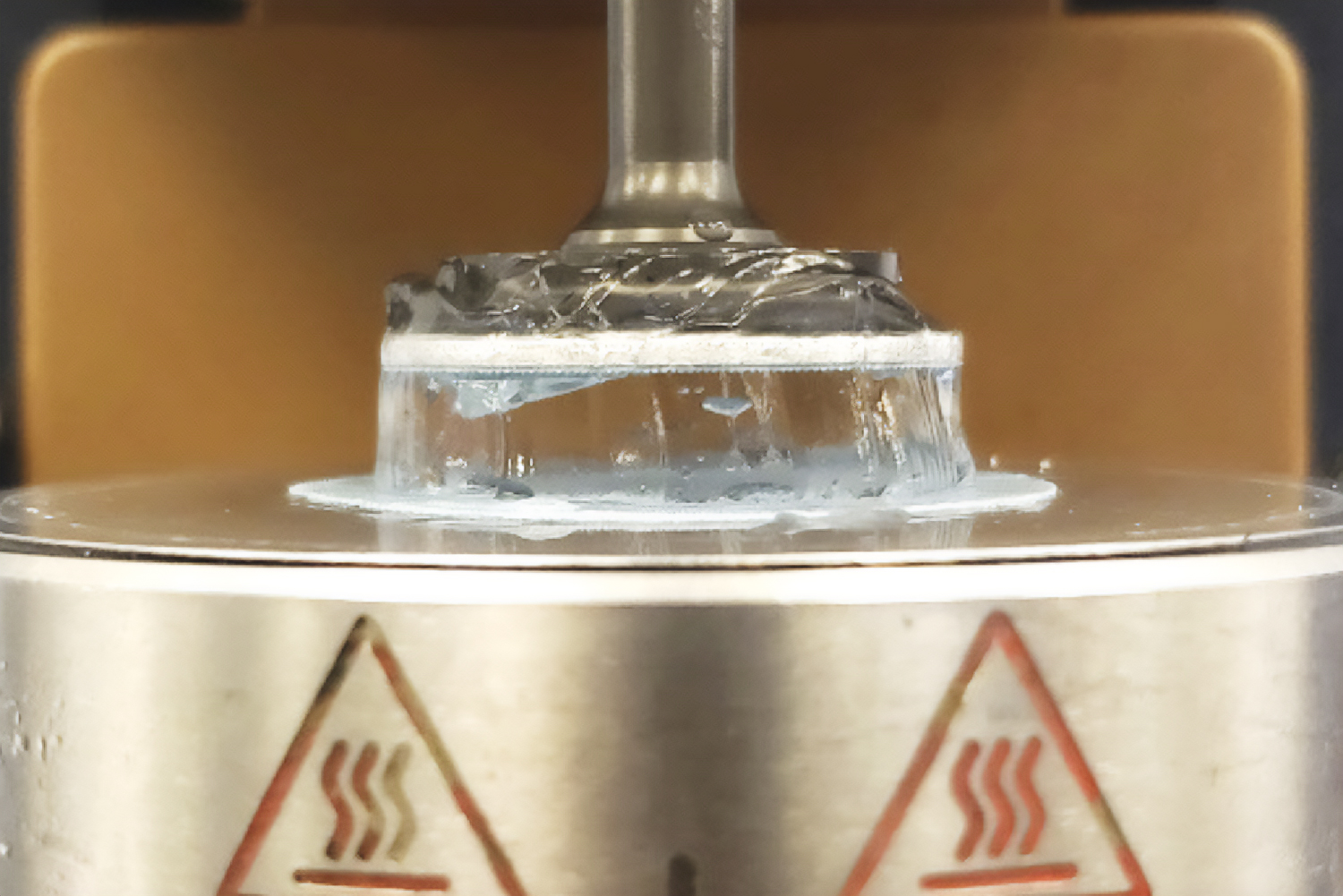

To test her hypothesis, she carried out experiments with two common soft glassy materials: hair gel and shaving cream. She made measurements of each material in a rheometer — an instrument consisting of two rotating plates that can twist and press a material together at precisely controlled pressures and forces that relate directly to the material’s internal stresses and strains.

In her experiments, she placed each material in the rheometer and spun the instrument’s top plate around to mix the material. Then she let the material settle, and then settle some more — much longer than one minute. During this time, she observed the amount of force it took the rheometer to hold the material in place. She reasoned that the greater the rheometer’s force, the more it must be counteracting any stress within the material that would otherwise cause it to shift out of its current state.

Over multiple experiments using this new protocol, Owens found that different types of soft glassy materials held a significant amount of residual stress, long after most researchers would assume the stress had dissipated. What’s more, she found that the degree of stress that a material retained was a reflection of the direction in which it was initially mixed, and when it was mixed.

“The material can effectively ‘remember’ which direction it was mixed, and how long ago,” Owens says. “And it turns out they hold this memory of their past, a lot longer than we used to think.”

In addition to the protocol she has developed to measure residual stress, Owens has developed a model to estimate how a material will change over time, given the degree of residual stress that it holds. Using this model, she says scientists might design materials with “short-term memory,” or very little residual stress, such that they remain stable over longer periods.

One material where she sees room for such improvement is asphalt — a substance that is first mixed, then poured in molten form over a surface where it then cools and settles over time. She suspects that residual stresses from the mixing of asphalt may contribute to cracks forming in pavement over time. Reducing these stresses at the start of the process could lead to longer-lasting, more resilient roads.

“People are inventing new types of asphalt all the time to be more eco-friendly, and all of these will have different levels of residual stress that will need some control,” she says. “There’s plenty of room to explore.”

This research was supported, in part, by MIT’s Postdoctoral Fellowship for Engineering Excellence and an MIT Mathworks Fellowship.