Everyone gets headaches. But not everyone gets cluster headache attacks, a debilitating malady producing acute pain that lasts an hour or two. Cluster headache attacks come in sets — hence the name — and leave people in complete agony, unable to function. A little under 1 percent of the U.S. population suffers from cluster headache.

But that’s just an outline of the matter. What’s it like to actually have a cluster headache?

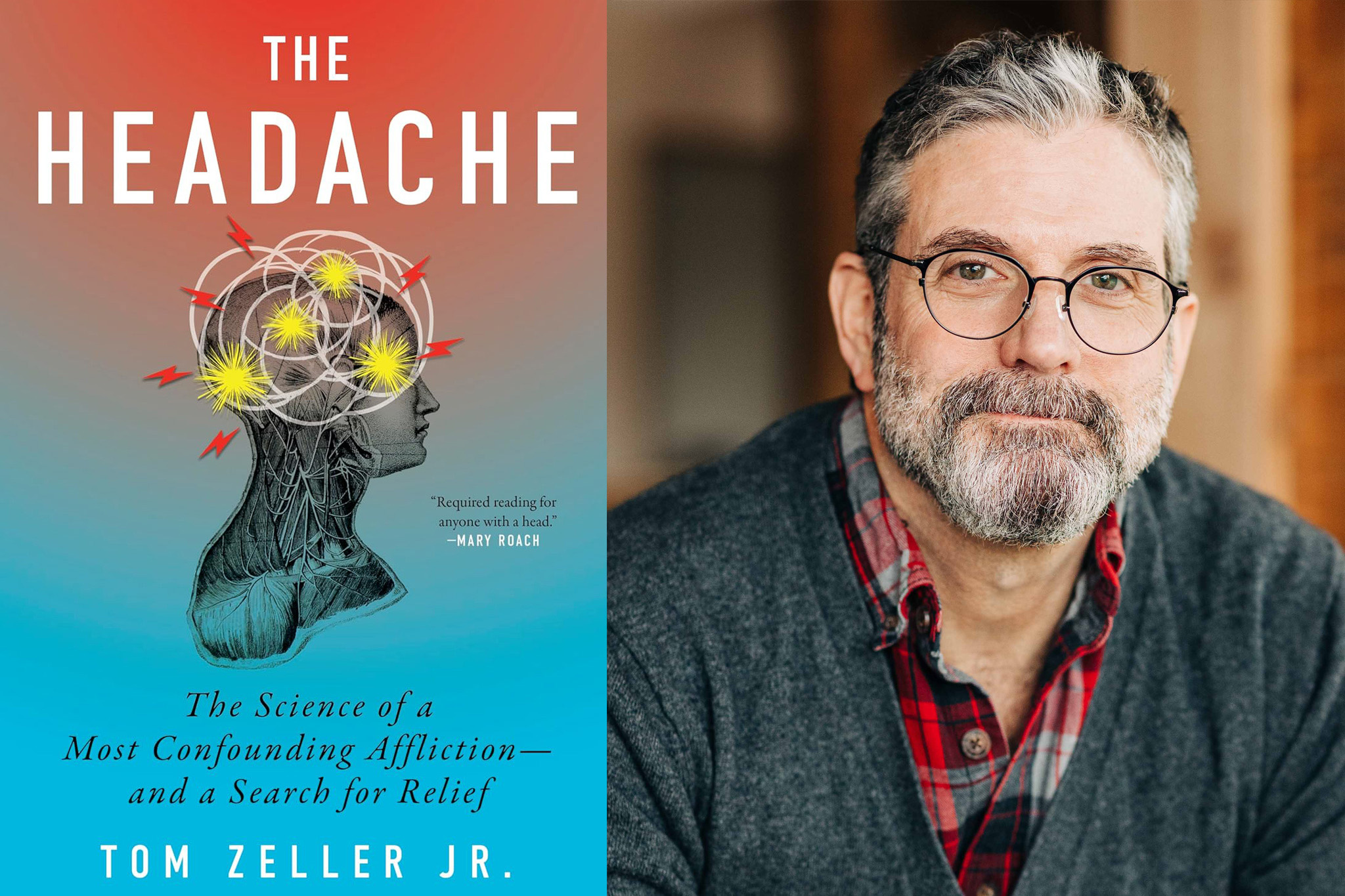

“The pain of a cluster headache is such that you can’t sit still,” says MIT-based science journalist Tom Zeller, who has suffered from them for decades. “I’d liken it to putting your hand on a hot burner, except that you can’t take your hand off for an hour or two. Every headache is an emergency. You have to run or pace or rock. Think of another pain you had to dance through, but it just doesn’t stop. It’s that level of intensity, and it’s all happening inside your head.”

And then there is the pain of the migraine headache, which seems slightly less acute than a cluster attack, but longer-lasting, and similarly debilitating. Migraine attacks can be accompanied by extreme sensitivity to light and noise, vision issues, and nausea, among other neurological symptoms, leaving patients alone in dark rooms for hours or days. An estimated 1.2 billion people around the world, including 40 million in the U.S., struggle with migraine attacks.

These are not obscure problems. And yet: We don’t know exactly why migraine and cluster headache disorders occur, nor how to address them. Headaches have never been a prominent topic within modern medical research. How can something so pervasive be so overlooked?

Now Zeller examines these issues in an absorbing book, “The Headache: The Science of a Most Confounding Affliction — and a Search for Relief,” published this summer by Mariner Books. Zeller is the editor-in-chief and co-founder of Undark, a digital magazine on science and society published by the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT.

One word, but different syndromes

“The Headache,” which is Zeller’s first book, combines a first-person narrative of his own suffering, accounts of the pain and dread that other headache sufferers feel, and thorough reporting on headache-based research in science and medicine. Zeller has experienced cluster headache attacks for 30-plus years, dating to when he was in his 20s.

“In some ways, I suppose I had been writing the book my whole adult life without knowing it,” Zeller says. Indeed, he had collected research material about these conditions for years while grappling with his own headache issues.

A key issue in the book is why society has not taken cluster headache and migraine problems more seriously — and relatedly, why the science of headache disorders is not more advanced. Although in fairness, as Zeller says, “Anything involving the brain or central nervous system is incredibly hard to study.”

More broadly, Zeller suggests in the book, we have conflated regular workaday headaches — the kind you may get from staring at a screen too long — with the far more severe and rather different disorders like cluster headache and migraine. (Some patients refer to cluster headache and migraine in the singular, not plural, to emphasize that this is an ongoing condition, not just successive headaches.)

“Headaches are annoying, and we tough it out,” Zeller says. “But we use the same exact word to talk about these other things,” namely, cluster headache and migraine. This has likely reinforced our general dismissal of severe headache disorders as a pressing and distinct medical problem. Instead, we often consider headache disorders, even severe ones, as something people should simply power through.

“There’s a certain sense of malingering we still attach to a migraine or [other] headache disorder, and I’m not sure that’s going away,” Zeller says.

Then too, about three-quarters of people who experience migraine attacks are women, which has quite plausibly led the ailment to “get short shrift historically,” as Zeller says. Or at least, in recent history: As Zeller chronicles in the book, an awareness of severe headache disorders goes back to ancient times, and it’s possible they have received less relative attention in modernity.

A new shift in medical thinking

In any case, for much of the 20th century, conventional medical wisdom held that migraine and cluster headache stemmed from changes or abnormalities in blood vessels. But in recent decades, as Zeller details, there has been a paradigm shift: These conditions are now seen as more neurological in origin.

A key breakthrough here was the 1980s discovery of a neurotransmitter called calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP. As scientists have discovered, CGRP is released from nerve endings around blood vessels and helps produce migraine symptoms. This offered a new strategy — and target — for combating severe head pain. The first drugs to inhibit the effects of CGRP hit the market in 2018, and most researchers in the field are now focused on idiopathic headache as a neurological disorder, not a vascular problem.

“It’s the way science works,” Zeller says. “Changing course is not easy. It’s like turning a ship on a dime. The same applies to the study of headaches.”

Many medications aimed at blocking these neurotransmitters have since been developed, though only about 20 percent of patients seem to find permanent relief as a result. As Zeller chronicles, other patients feel benefits for about a year, before the effects of a medication wear off; many of them now try complicated combinations of medications.

Severe headache disorders also seem linked to hormonal changes in people, who often see an onset of these ailments in their teens, and a diminishing of symptoms later in life. So, while headache medicine has witnessed a recent breakthrough, much more work lies ahead.

Opening up a discussion

Amid all this, one set of questions still tugging at Zeller is evolutionary in nature: Why do humans experience headache disorders at all? There is no clear evidence that other species get severe headaches — or that the prevalence of severe headache conditions in society has ever diminished.

One hypothesis, Zeller notes, is that “having a highly attuned nervous system could have been a benefit in our more primitive state.” Such a system may have helped us survive, in the past, but at the cost of producing intense disorders in some people when the wiring goes a bit awry. We may learn more about this as neuro-based headache research continues.

“The Headache” has received widespread praise. Writing in The New Yorker, Jerome Groopman heralded the “rich material in the book,” noting that it “weaves together history, biology, a survey of current research, testimony from patients, and an agonizing account of Zeller’s own suffering.”

For his part, Zeller says he is appreciative of the attention “The Headache” has generated, as one of the most widely-noted nonfiction books released this summer.

“It’s opened up room for a kind of conversation that doesn’t usually break through into the mainstream,” Zeller says. “I’m hearing from a lot of patients who just are saying, ‘Thank you for writing this.’ And that’s really gratifying. I’m most happy to hear from people who think it’s giving them a voice. I’m also hearing a lot from doctors and scientists. The moment has opened up for this discussion, and I’m grateful for that.”