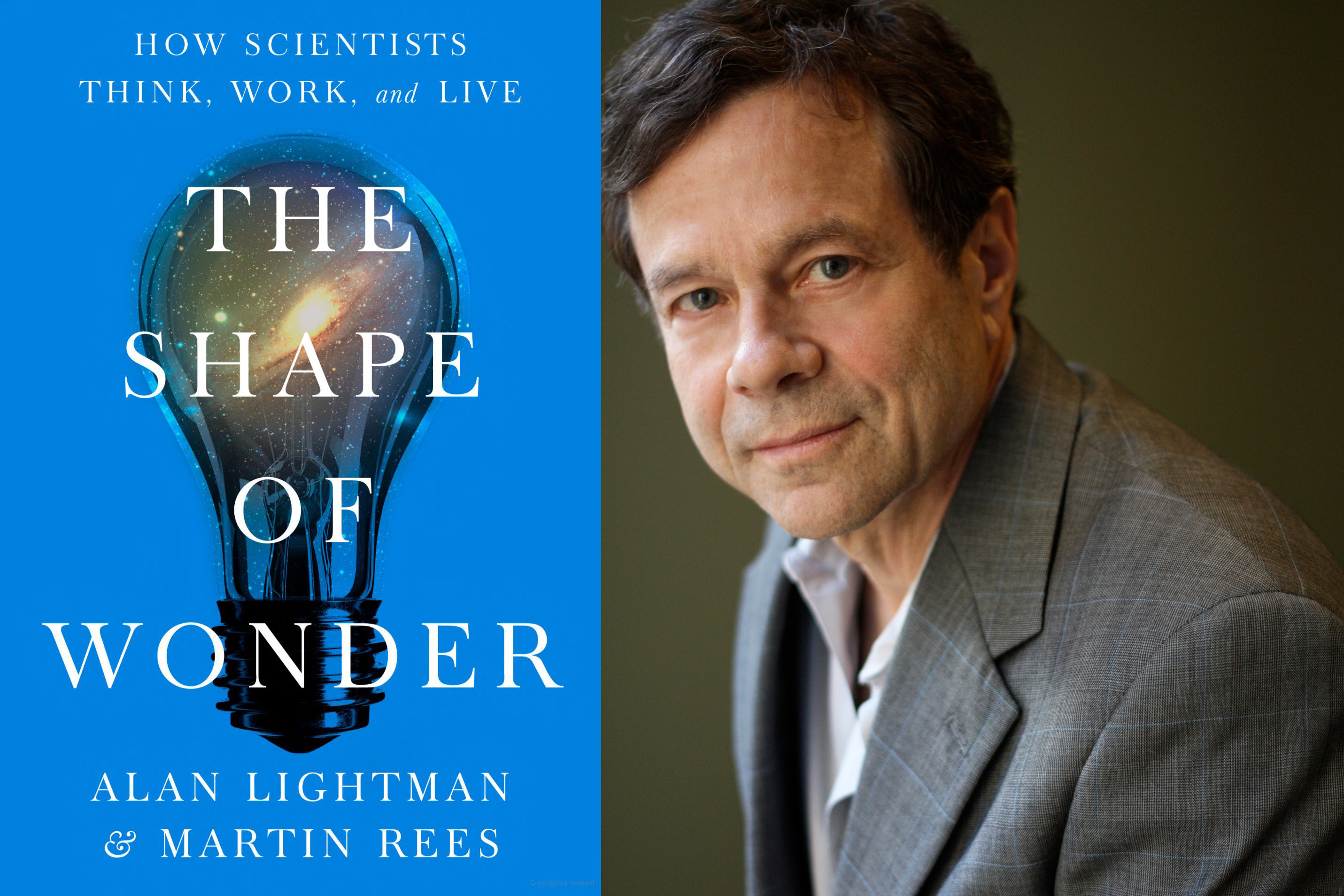

Alan Lightman has spent much of his authorial career writing about scientific discovery, the boundaries of knowledge, and remarkable findings from the world of research. His latest book “The Shape of Wonder,” co-authored with the lauded English astrophysicist Martin Rees and published this month by Penguin Random House, offers both profiles of scientists and an examination of scientific methods, humanizing researchers and making an affirmative case for the value of their work. Lightman is a professor of the practice of the humanities in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing Program; Rees is a fellow of Trinity College at Cambridge University and the UK’s Astronomer Royal. Lightman talked with MIT News about the new volume.

Q: What is your new book about?

A: The book tries to show who scientists are and how they think. Martin and I wrote it to address several problems. One is mistrust in scientists and their institutions, which is a worldwide problem. We saw this problem illustrated during the pandemic. That mistrust I think is associated with a belief by some people that scientists and their institutions are part of the elite establishment, a belief that is one feature of the populist movement worldwide. In recent years there’s been considerable misinformation about science. And, many people don’t know who scientists are.

Another thing, which is very important, is a lack of understanding about evidence-based critical thinking. When scientists get new data and information, their theories and recommendations change. But this process, part of the scientific method, is not well-understood outside of science. Those are issues we address in the book. We have profiles of a number of scientists and show them as real people, most of whom work for the benefit of society or out of intellectual curiosity, rather than being driven by political or financial interests. We try to humanize scientists while showing how they think.

Q: You profile some well-known figures in the book, as well as some lesser-known scientists. Who are some of the people you feature in it?

A: One person is a young neuroscientist, Lace Riggs, who works at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT. She grew up in difficult circumstances in southern California, decided to go into science, got a PhD in neuroscience, and works as a postdoc researching the effect of different compounds on the brain and how that might lead to drugs to combat certain mental illnesses. Another very interesting person is Magdalena Lenda, an ecologist in Poland. When she was growing up, her father sold fish for a living, and took her out in the countryside and would identify plants, which got her interested in ecology. She works on stopping invasive species. The intention is to talk about people’s lives and interests, and show them as full people.

While humanizing scientists in the book, we show how critical thinking works in science. By the way, critical thinking is not owned by scientists. Accountants, doctors, and many others use critical thinking. I’ve talked to my car mechanic about what kinds of problems come into the shop. People don’t know what causes the check engine light to go on — the catalytic converter, corroded spark plugs, etc. — so mechanics often start from the simplest and cheapest possibilities and go to the next potential problem, down the list. That’s a perfect example of critical thinking. In science, it is checking your ideas and hypotheses against data, then updating them if needed.

Q: Are there common threads linking together the many scientists you feature in the book?

A: There are common threads, but also no single scientific stereotype. There’s a wide range of personalities in the sciences. But one common thread is that all the scientists I know are passionate about what they’re doing. They’re working for the benefit of society, and out of sheer intellectual curiosity. That links all the people in the book, as well as other scientists I’ve known. I wish more people in America would realize this: Scientists are working for their overall benefit. Science is a great success story. Thanks to scientific advances, since 1900 the expected lifespan in the U.S, has increased from a little more than 45 years to almost 80 years, in just a century, largely due to our ability to combat diseases. What’s more vital than your lifespan?

This book is just a drop in the bucket in terms of what needs to be done. But we all do what we can.